Mila Panić is a Bosnian-born artist and stand-up comedian. Her artist's practice ranges from personal documentation to poetic visual and discursive elements through which she creates a cycle that interprets the various inheritances of migration. Within the Festival Mila Panić shows her work “Südost Paket” at the Lapidarium and performs as a stand-up comedian.

Your work "Südost Paket" connects personal and collective memory of migration through the recurring symbol of the wheel. How do you decide which items to include?

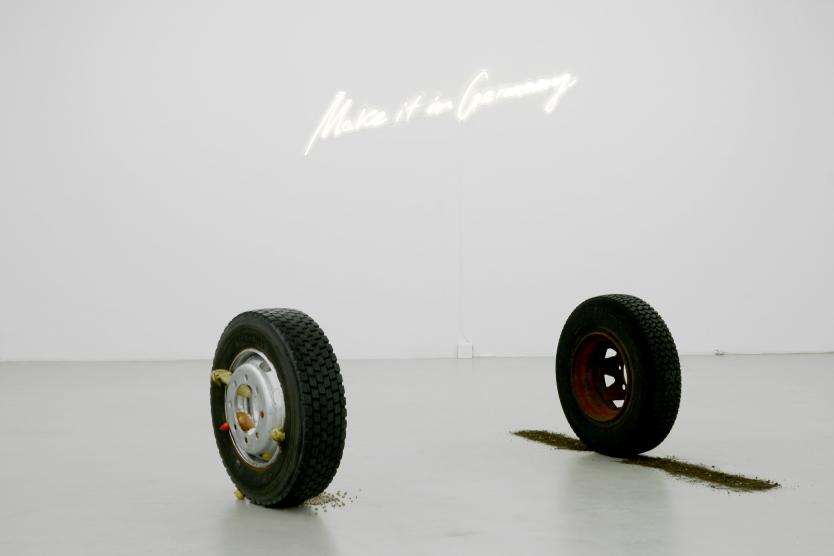

I choose the objects by feeling. Items that remind me of home, or funny stories and events that I have seen or heard about, trips and smuggling with buses from Bosnia. These objects became a personification of our identity and folklore, and together with the bus tire, they are like a monument for me. A monument to the microcosm that gets created in the bus during the 20-24 hours of crossing the border (physically and morally) while travelling from Bosnia to Germany and vice versa. Many things happen on that bus. A lot of fear, anxiety, sadness, smuggling of simple goods and knowledge in some way, but also laughter, excitement and solidarity—depending on the direction of the bus.

For "Südost Paket" you fill tires with symbolic goods like cigarettes and sweets. What do these specific items reveal about memory, value, and imagined prestige in the migrant experience?

When people migrate, it often feels as though they are smuggling their future out of one place and into another. The vague promise of a possible destiny, paired with the weight of high expectations, is a powerful reason to leave. This imagined, "smuggled" future carries the hope that it will eventually appear and fulfil itself somewhere in a new, yet undefined space. That space—whether a city, region, or country—can, of course, be described through hard data: geography, statistics, GDP rankings, quality of life, career opportunities, average income, and so on; These metrics define a place as desirable or not—and usually, the higher the scores, the more it draws migrants in. The lower-scoring ones, by contrast, are marked as undesirable.

Südost Paket questions this binary by reversing the flow of value. Through the act of ‘smuggling’, it challenges the assumed direction of desire. The items we used—cigarettes, sweets, everyday things from Bosnia and Herzegovina—aren’t rare or luxurious in the traditional sense. But they carry emotional and symbolic weight. They become artefacts of this imagined “better” place. Except here, the direction is reversed—we’re smuggling from BiH to Germany, not the other way around (as usually assumed). That reversal disrupts the usual narrative of migration as upward movement and challenges how we assign value to space.

The work points to a different understanding of geography—not as fixed, bordered land, but as imagined, deeply personal, unstable, and shaped by experience.

By embedding humour, mobility, and resistance into your work, you also destabilise fixed narratives of place and belonging. Besides using objects and making sculptures, you also bring stand-up comedy into art institutions. What role does laughter play in your practice?

To me, stand-up comedy is just another medium of contemporary art. Whether using a joke or an installation, the goal is the same: to make the audience rethink social norms and question power structures. In my case, jokes seem to be my preferred language. Jokes have simply 'infected' my whole life. There is not a moment when I am not working and collecting material. Over time, they’ve found their way into my drawings and exhibitions—spaces where active laughter is rarely heard.

I like the idea of being loud in those quiet spaces, of making people laugh where they least expect it. Laughter is deeply social, but it can also be shameful. When we laugh together, we enter into a kind of collective agreement—one that acknowledges our fears, hopes, frustrations, and, maybe most importantly, our capacity to heal and change.

Of course, the audience in galleries or institutions is more challenging—and definitely more restricted—than in a comedy club. But that tension is also where some of the most interesting moments happen.